THE BACHKA RUSYNS OF YUGOSLAVIA, THE LEMKOS OF POLAND

THEIR LANGUAGES AND THE QUESTION OF THEIR TRANSLITERATION AND SUBJECT CATALOGING

copyright 1998 - BOGDAN HORBAL HORBAL@WORLDNET.ATT.NET

INTRODUCTION

In light of contentious debate among scholars on Carpatho-Rusyns ethnonational identity, an American cataloger of Slavic materials will sooner or later face the problem of allocating a subject heading for materials dealing with Carpatho-Rusyns. At present there is no consensus as to whether or not a Carpatho-Rusyn language can - or even should - exist. Despite this a number of publications have been written in the Carpatho-Rusyn vernacular speech. How should these materials be transliterated?

As a matter of fact, the author of this paper has already witnessed "a cry for help", sent via e-mail to the Slavic and Baltic Division of the New York Public Library. A desperate cataloger wrote: "I have this book published in Novi Sad, Yugoslavia. It is in Cyrillic letters, in language similar to Ukrainian, but it is not quite Ukrainian. What is this language, any ideas?". A need clearly exists for resolving this question.

CARPATHO-RUSYNS

Carpatho-Rusyns live in the very heart of Europe, along the northern and southern slopes of the Carpathian Mountains. Their homeland, known as Carpathian Rus', is situated at the crossroads where the borders of Ukraine, Slovakia, and Poland meet. Aside from those countries, there are smaller numbers of Carpatho-Rusyns in Romania, Hungary, Yugoslavia, and the Czech Republic. In no country do Carpatho-Rusyns have an administratively distinct territory.

This Eastern Slavic group numbers approximately 1.2 million. It is believed that approximately 600,000 Carpatho-Rusyns live in North America. At present, Carpatho-Rusyns living in the homelands are considered either part of the Ukrainian nationality or a separate, distinct nationality. Until 1945, Carpatho-Rusyn history developed along lines distinct from Ukrainian territories. After the Second World War this unique historical development has been still in evidence among Carpatho-Rusyns in former Yugoslavia (present day Serbia and Croatia), and the United States. Since the fall of communism in the Eastern Europe (1989) Carpatho-Rusyn national life has undergone an energetic rebirth in Poland, Slovakia, Ukraine, and Hungary.

The Carpatho-Rusyn four dialects are classified as East Slavic and are closely related to Ukrainian. Because their speakers live in a borderland region, Carpatho-Rusyn dialects are heavily influenced by the surrounding Polish, Slovak, and Hungarian vocabularies. These influences from both the east and west, together with numerous terms from the Church Slavonic liturgical language and dialectal words unique to Carpatho-Rusyns, are what distinguish their spoken language from other East Slavic languages like Ukrainian. In contrast to their West Slavic (Polish and Slovak), Magyar, and Romanian neighbors, Carpatho-Rusyns use the Cyrillic alphabet.

When Carpatho-Rusyns began to publish books in the seventeenth century, they were written either in the Rusyn vernacular or in Church Slavonic, a liturgical language (functionally similar to Latin) used by East Slavs and South Slavs who were of an Eastern Christian religious orientation. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Carpatho-Rusyn writers continued to use the Rusyn vernacular and also began to use Russian and Ukrainian as their literary language. The so-called "language question" was always closely related to the problem of national identity.1

Today there are only two national orientations - Rusyn and Ukrainian. The Ukrainian orientation argues that Rusyns are a branch of the Ukrainian nationality and that a distinct Carpatho-Rusyn nationality cannot and should not exist. A third, historically strong but now dead identity "option" was the Russophile one. The supporters of that ideology believed that Rusyns were a branch of a "Greater Russian" nation.2

RUSYNS OF VOJVODINA AND THEIR LITERARY STANDARD

The oldest Rusyn immigrant community is in the Vojvodina (historic Backa and Srem) region of former Yugoslavia, that is, present-day northern Serbia and far eastern Croatia. A number of Carpatho-Rusyns moved there from their Carpathian home during the mid-eighteenth century. This community numbers today approximately 30,000 people, majority of whom live within the borders of Serbia.3

Up to 1914 Vojvodinian Rusyns had based their educational practices upon the materials produced in the Carpathian homeland.4 At the turn of the centuries, however a few publications in vernacular Vojvodinian Rusyn speech appeared.5 In 1919 the Vojvodinian Rusyn community decided to elevate its colloquial language to the level of a literary language. The Rusyn Popular Education Society was established and the first grammar was published six years later.6 The Vojvodinian Rusyn vernacular language was at that time already used in publications.7 During the next decades, there was lots of discussion on which language the Rusyn literary standard should be modelled on.8 It was, however "the joy of having education in our own language", as it was stated by one of the Rusyn leaders, that prevailed and in fact ended the subordinate status of the Rusyn language and culture to those of related peoples, whether Russian, Ukrainian, or Slovak. The more recent standardization of the Rusyn language took place in the late sixties. The special Orthography Commision9 published among others a primer and the orthography.10 In the 70-ties the gymnazia in Ruski Kerestur was established, and it was followed by a Department of Rusyn Language and Literature at the University of Novi Sad (1985).

There are several theories regarding the origin and affilation of the Vojvodinian Rusyn language.12 There are also many difficulties in determining the linguistic status of this language.13 It is, however true that this language successfully withstood the test of history and that's why it deserves full recognition. It has all the basic attributes and performs the same functions of a developed standardized language; it is used in all levels of local and regional administration for political, legislative and judicial matters; in all forms of the media (newspapers, periodicals, radio, television); in education from pre-school through the highest levels; and in scholarly, cultural, and religious institutions and their publications.

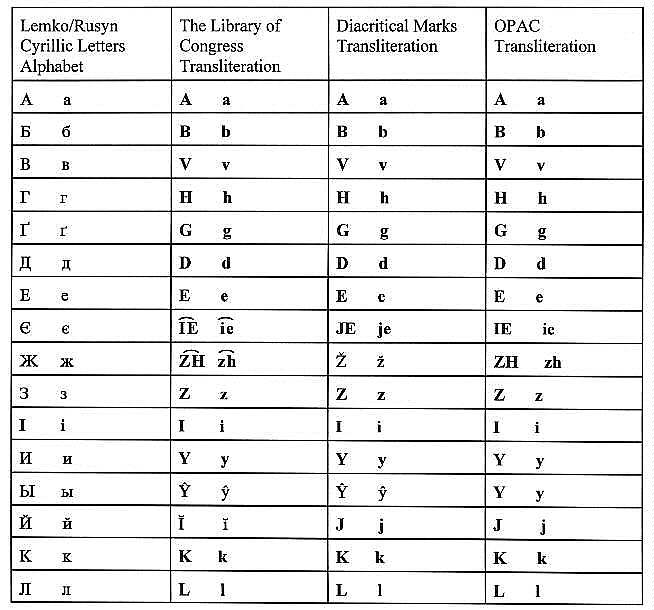

The alphabet of the Vojvodinian Rusyn language consists of 32 letters.14 The following transliteration systems should be use:

HELPFUL HINTS FOR A CATALOGER OF VOJVODINIAN RUSYN MATERIALS

The major issue here seems to be the recognition of what is written in Vojvodinian Rusyn. Most of the materials published in this language come out of Novi Sad, and some out of Ruski Kerestur. All of them use the Cyrillic alphabet which is almost identical to the Ukrainian alphabet. The only difference is that the Vojvodinian Rusyn does not use "i". As far as transliteration is concerned there is only one difference from the transliteration of Ukrainian: the Vojvodinian Rusyn "[letter not displayed]" should be transliterated as "i", and not as "y", as it is in the case of the Ukrainian language.

THE LEMKOS OF POLAND

The first attempts to use the Lemko vernacular speech in writing dates back to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.18 In 1871 Mykola Astriab wrote a series of short articles in Lemko on different aspects of the Lemko verncular speech.19 This uncodified speech was used by the editorial board of a weekly newspaper Lemko (1911-1913). It was and has been used by a number of Lemko publications put out by the Lemko immigration in America. It was, however not before the thirties, that the Lemko inteligencia undertook efforts to create a standard Lemko literary language for use in schools and publications.

Founded in 1933, the Lemkian Association responded to Ukrainian ethnonational activism in the schools with a program for teaching of Lemko vernacular speech. Metodyj Trokhanowskii (1885-1947) had compiled two textbooks in the Lemko vernacular,20 which were subsequently introduced into the primary schools of the region. The Association also put out a number of publications in Lemko vernacular, including a weekly Lemko (1934-39) and calendars.21

During WWII the Lemko Region witnessed its ukrainization carried out by Ukrainian refugees from Eastern Galicia and supported by the Nazis.22 After the war the Lemko/Rusyns faced even greater difficulties. Since the imposition of Soviet-dominated Communist rule throughout East Central Europe, the Rusyn language was banned in all countries where Rusyns lived, except in Yugoslavia. In the Soviet Ukraine, Czechoslovakia and Poland, Rusyns were administratively declared to be Ukrainians and all publications and schooling intended for them had to be carried out in Ukrainian. Any efforts to have some form of Rusyn used in publications, schools, or public life was considered to be illegal ("counterrevolutionary"). This was supposed to end the so called "language question" among Carpatho-Rusyns.

The collapse of Communism released the repressed but unresolved question of national identity and language among Rusyns. When, after 1989, Rusyn language newspapers appeared in Poland (Besida), Slovakia and Ukraine, and the Rusyn cultural movement became stronger, it adopted as its primary goal the codification of a standardized Rusyn literary language.

The Rusyn oriented Lemkos in Poland founded the Lemko Association (Stovaryshynia Lemkiv) in 1989. One of the major goals of this organization is the standardization of the Lemko vernacular. The Association's Committee of National Enlightenment started its activity with a revised, updated reissuing of the Trokhanovskii's Primer (1991). During the following year a working copy of a Grammar was printed,23 and a year later a Lemko-Polish Dictionary.24 Myroslava KHomiak prepared a number of language books25 intented for the first and second grade of primary schools and the Lemko vernacular was introduced in a few schools in Poland.

The alphabet used by Lemko/Rusyn language consists of 32 letters and two signs.26

The following transliteration systems should be used for it:

HELPFUL HINTS FOT A CATALOGER OF LEMKO-RUSYN MATERIALS

Present day Lemko/Rusyn materials come almost exclusively out of Poland.

They are written in Cyrillic letters. The alphabet used by them is almost

the same as the one used by the Ukrainian language. The only two differences

between the Lemko/Rusyn and Ukrainian is that the Lemko\Rusyn uses "

![]() ", and does not use "i",

and vice versa. Thus, the simplest way to recognize Lemko/Rusyn is to look

for letter "

", and does not use "i",

and vice versa. Thus, the simplest way to recognize Lemko/Rusyn is to look

for letter "![]() ". The transliteration

systems remain basically the same as those which apply to the transliteration

of the Ukrainian language, except that "

". The transliteration

systems remain basically the same as those which apply to the transliteration

of the Ukrainian language, except that "![]() " should be transliterated as "y ".

" should be transliterated as "y ".

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS SUBJECT HEADINGS FOR CARPATHO-RUSYNS

Carpatho-Rusyns are described by several different names. The most popular among them are: Rusyns, Rusnaks, Ruthenians, Lemkos (Lemky), Boykos (Boiky), Hutsuls (Hutsuly), Carpatho-Russians, Ugro-Rusyns, Ugro-Russians, Carpatho-Ukrainians. The Library of Congress Subject Headings offer the following headings: Carpatho-Rusyns, Ruthenians, Lemky-Lemkivshchyna, Boiky-Boikivshchyna, and Hutsuly-Hutsulshchyna. There is, however a number of mistakes in the approach to the question of subject headings for Carpatho-Rusyns. These are the proper versions of headings for Carpatho-Rusyns:

1.Carpatho-Rusyns (May Subd Geog)27

Here are entered works on Ruthenian inhabitiants of Transcarpathia [(Ukraine), Lemkivshchyna (Poland and Slovakia), and their immigrant communities in: Vojvodina (Yugoslavia), Croatia, North America and other countries.]

UF Carpatho-Rusins

Carpatho-Russians

Carpatho-Ruthenians

Subcarpathian Rusyns

Uhro-Rusins

BT Ethnology-Europe, Eastern

[Ethnology-Carpathian Mountains]

[Ethnology-Europe, Southern]

[Ethnology-United States]

[Ethnology-Canada]

[NT Lemky]

[Boiky]

[Hutsuly]

RT Ruthenians

2.Ruthenians28

Here are entered works on Ukrainian and Carpatho-Rusyn residents in the territory comprising the former Austro-Hungarian Empire. Works on their descedants after 1918 are entered under Ukrainians and Carpatho- Rusyns.

UF Rusini

Rusins

Rusiny

Rusnatsi

[Rusnatsy]

Rusyns Rusyny

Ruthenen

Ruthenes

BT Ethnology-Europe, Eastern

[Ethnology-Carpathian Mountains]

[Ethnology-Europe, Southern]

[Ethnology-United States]

[Ethnology-Canada]

RT Carpatho-Rusyns

Ukrainians

3.[Lemkovyna (Poland and Slovakia)]29

UF Lemkian Region (Poland and Slovakia)

Lemkivshchyna (Poland and Czechoslovakia) [Former heading]

Lemko Region (Poland and Slovakia)

Lemkovina (Poland and Slovakia)

[Lemkivshchyna (Poland and Slovakia)]

Lemkowszczyzna (Poland and Slovakia)

4.Lemky (May Subd Geog)

UF Lemaky

Lemki [Former heading]

Lemkians

Lemkos

Lemkowie

BT Ethnology-Carpathian Mountains

Ethnology-Poland

Ethnology-Slovakia

[Ethnology-United States]

[Ethnology-Canada]

Ukrainians

[Carpatho-Rusyns]30

RT Ruthenians

4.Boikivshchyna (Ukraine, [Poland and Slovakia]) 31

UF Boiko Region (Ukraine [Poland and Slovakia])

[Bojkowszczyzna (Ukraine, Poland and Slovakia)]

5.Boiky [May Subd Geog]

UF Boiki

Boikos

BT Ethnology-Carpathian Mountains

Ethnology-Ukraine

[Ethnology-Poland]

[Ethnology-Slovakia]

[Ethnology-United States]

[Ethnology-Canada]

Ukrainians

[Carpatho-Rusyns]

RT Ruthenians

6.Hutsulshchyna (Ukraine) 32

UF Huculszczyzna (Ukraine)

Hutsul Region (Ukraine)

7.Hutsuls (Ukraine) 33

UF Hootzools

Huculs

Hutzuls

Huzule

Huzuls

[Huculi]

BT Ethnology-Carpathian Mountains

Ethnology-Ukraine

[Ethnology-United States]

[Ethnology-Canada]

[Ukrainians]

[Carpatho-Rusyns]

[RT Ruthenians]

It is interesting that Carpatho-Rusyns from Vojvodina are not recognized in the system of Library of Congress Subject Headings. Although their language is a standardized literary one, the subject heading it usually gets is the following:

Author Kolesarov, IUlyian Dragen,

Title Rusky slovar davneishyk vyrazokh.

Subject Ukrainian language -- Etymology -- Dictionaries.

Neither "the Ukrainian" subject heading, nor the sometimes assigned "Ruthenian" one (see below) is appropriate:

Author Kolesarov, IUlyian Dragen,

Title Pratky u Rusnatsokh.

Subject Folk songs, Ruthenians.

CONCLUSIONS

The Carpatho-Rusyns are an ethnic minority that due to its numerically small size and unimportance in international relationships, is almost completely unknown. The group has also been overshadowed by its closely related neighbor - Ukrainians. The Ukrainians tend to view the group as a part of the Ukrainian ethnos. The Ukrainian attitude toward Carpatho-Rusyns without a doubt influences how others view them. Regardless of all this, Carpatho-Rusyns have, however received some attention in the Library of Congress Subject Headings system. There is unfortunately some confusion in this system as far as concerns the headings on Carpatho-Rusyns. The implementation of existing rules could also be improved. It is encouraging, however that some catalogers make an extra effort and assign the right subject headings to works on Carpatho-Rusyns. See for example these bibliographic records from the OPAC of the New York Public Library:34

Author Panko, IUrii.

Title Rusynsko-rusko-ukrainsko-slovensko-polskyi slovnyk lingvistichnykh terminiv.

Subject Carpatho-Rusyn language -- Dictionaries -- Polyglot.

Author Benedek, Andras.

Title Karpatalja tortenete es kulturtortenete.

Subject Carpatho-Rusyns -- Civilization.

Title Nasha Knyzhka.

Subject Carpatho-Rusyn Literature -- United States.

Author Magocsi, Paul R.

Title Rusyny na Slovensku : istorychnyi perehliad.

Subject Carpatho-Rusyns -- Slovakia -- History

BIBLIOGRAPHY

American National Standard System for the Romanization of Slavic Cyrillic Characters: Approved April 12, 1976. New York: ANSI, 1976.

Astriab M. "Kol'ko slov o lemkovskoi besidi," Uchytel', 3 November (new calendar) 1871, 170; 10 November 1871, 174; 17 November 1871, 174; 23 November 1871, 178; 30 November 1871, 182; 7 December 1871 1871, 186; 14 December 1871, 21 December 1871, 191; 28 December 1871, 194; 4 January 1872, 199; 11 January 1872, 202.

Custer, Richard D. "Our Rusyn Language=Nash Rusyns'kyi iazyk", The New Rusyn Times, 6, no.1 (January/February 1997), 7-9.

Duc'-Fajfer, Olena. "The Lemkos in Poland." In The Persitence of Regional Cultures. Rusyns and Ukrainians in Their Carpathian Homeland and Abroad, Paul Robert Magocsi, ed. 83-105. Fairview, NJ: The Carpatho-Rusyn Research Center, 1993.

Dzvinka Mykhailo. "Literatura pivnichnykh zemel'." In Lemkivshchyna, ed.Bohdan O.Strumins'kyi ed. vol.1, 379-387. New York: The Shevchenko Scientific Society, 1988.

Dukhnovych, Aleksander. Bukvar', Przemysl, 1850.

----------.Knyzhytsia chytalnaia dlia nachynaiushchykh. Buda, 1847, 2nd.rev.ed., 1850, 3rd.rev.ed., 1853.

Kochish, Mikola. Pravopis ruskoho iazika. Shkolske vidanie. Novi Sad: Pakraïnski Zavod za Vidavanie Uchebnïkokh, 1971.

Kostel'nik, Havriïl. Gramatika. 1925. reprinted in Novi Sad: Proza, 1975.

Kostel'nik Homzov, Gabriel. Iz moioho valala: sonetny veniets. ZHovkva, 1904.

Kubijovych, Volodymyr. Ukraintsi v Heneralnii Huberniï 1939-41. Chicago: Mykola Denysiuk Publishing Company, 1975.

Labosh, Fedor. Istoriia Rusinokh Bachkei, Srimu i Slavoni , 1745-1918. Vukovar: Soiuz rusinokh i ukra ntsokh horvatske , 1979.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 19th.ed. Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1996.

Magocsi, Paul Robert. The Language Question Among the Subcarpathian Rusyns. Fairview, NJ: The Carpatho-Rusyn Research Center, 1979.

----------. The Shaping of a National Identity. Cambridge-London: Harvard University Press, 1978.

Medješi, Ljubomir. "The Problem of Cultural Borders in the History of Ethnic Groups: The Yugoslav Rusyns." In The Persitence of Regional Cultures. Rusyns and Ukrainians in Their Carpathian Homeland and Abroad, Paul Robert Magocsi, ed. 139-163. Fairviev, NJ: The Carpatho-Rusyn Research Center, 1993.

Oleiar, IAkim and Mikola Kochish, Bukvar za pershu klasu osnovnei shkoli z ruskim nastavnim iazikom. Novi Sad: Pakraïnski Zavod za Vidavanie Uchebnïkokh, 1967.

Randall, Barry K. ed. and comp., ALA-LC Romanization Tables: Transliteration Schemes for Non-Roman Scripts Approved by the Library of Congress and the American Library Association. Washington: Cataloging Distribution Service, Library of Congress, 1991.

[Trokhanovskii, Metodyi]. Bukvar. Persha knyzhechka dlia narodn kh shkol. Lvov: Derzavne V davnytstvo Knyzhok SHkol'n kh, 193.

[----------]. Druha knyzhechka dlia narodnykh shkol. Lvov: Derzavne V davnytstvo Knyzhok Shkol'n kh, 1936.

Trukhan, Myroslav. Ukraintsi v Pol'shchy pis'lia druhoii svitovoii viiny 1944-1984. New York-Paris-Sydney-Toronto: The Shevchenko Scientific Society, 1990.

Tseng, Sally C. comp., LC Romanization Tables and Cataloging Policies. Metuchen, N.J.: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1990.

Varga, Evfemiia. Moia persha knizhka. CHitanka za pershu klasu osnovnei shkoly. Ruski Kerestur: Ruske slovo, 1965.

Verkhrats'kyi, Ivan. Pro hovor halytskykh Lemkiv. L'viv: NTSH, 1902.

Vrabel', Mikhayl. Bukvar', Uzhhorod, 1898.

----------. Russkii solovei: narodnaia lira ili sobranie narodnykh piesnei na raznykh ugro- russkikh nariechiiakh. Uzhhorod, 1890.

Zazuliak, Michael. "240 Anniversary of Rusin Kerestur", Trembita, 6, no.1 (March, 1994), 5-6,

Zwoliñski, Jaroslaw. Rapsodia dla £emków, Koszalin: Urz¹d Wojewódzki, 1994.